Quellenangabe:

Immigration Detention in Libya: “A Human Rights Crisis” (vom 06.09.2018),

URL: http://no-racism.net/article/5451/,

besucht am 19.07.2025

[06. Sep 2018]

Immigration Detention in Libya: “A Human Rights Crisis”

The Global Detention Project published a worth reading report about the history and current situation of detention in Libya (:: PDF). Libya is notoriously perilous for refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants, who often suffer a litany of abuses, including at the country’s numerous detention facilities.

Conditions at these facilities, many of which are under the control of militias, are deplorable. There are frequent shortages of water and food; over-crowding is endemic; detainees can experience physical mistreatment and torture; forced labour and slavery are rife; and there is a stark absence of oversight and regulation. Nevertheless, Italy and the European Union continue to strike controversial migration control deals with various actors in Libya aimed at reducing flows across the Mediterranean. These arrangements include equipping Libyan farces to “rescue” intercepted migrants and refugees at sea, investing in detention centres, and paying militias to control migration.

Following the Key Concerns and the Introduction, :: download the full report as PDF here.

Key Concerns

- Refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants are regularly exposed to indefinite detention in centres run by the Interior Ministry's Department for Combating Illegal Immigration or local militias;

- Detention conditions across the country are a matter of “grave concern,” according to the UN, as detainees are forced to live in severely overcrowded facilities with little food, water, or medical care, and suffer physical abuse, forced labour, slavery, and torture;

- The automatic placement of asylum seekers and migrants intercepted at sea in detention centres places them at risk of human rights abuses, which could be attenuated by expanding the use of shelters and other non-custodial measures that have been proposed by international experts;

- There do not appear to be any legal provisions regulating administrative forms of immigration detention and there is an urgent need for the country to develop a sound legal framework for its migration polices that is in line with international human rights standards;

- There is severely inadequate data collection by national authorities concerning the locations and numbers of people apprehended by both official agencies and non-state actors;

- Women and children are not recognised as requiring special attention and thus they remain particularly vulnerable to abuse and ill-treatment, including rape and human trafficking;

- Italy and the European Union continue to broker deals with various Libyan forces to control migration despite their involvement in severe human rights abuses and other criminal activities.

1. Intoduction

The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights has characterised the plight of refugees and migrants in Libya as a “human rights crisis.”[1] Since the beginning of the 2011 civil war in Libya, the country has experienced on-going armed conflict between rival militias and government forces. The resulting lawlessness has enabled armed groups, criminal gangs, smugglers, and traffickers to control much of the flow of migrants,[2] sometimes with the direct backing of :: Italy and other European countries.[3] Those detained—who according to various reports can number between 10,000-20,000 at any given time[4]—often face severe abuses, including rape and torture, extortion, forced labour, slavery, dire living conditions, and extra-judicial execution.[5]

Among the migrants who are particularly at risk of abuse in Libya are those from sub-Saharan countries, who are subjected to widespread racism, which has been exasperated by the crisis.[6] The International Organisation for Migration (IOM) has reported on the emergence of burgeoning “slave markets” along migrant routes into Libya where sub-Saharan migrants are “being sold and bought by Libyans, with the support of Ghanaians and Nigerians who work for them.”[7]

- “Migrants have become a commodity to be captured, sold, traded, and leveraged. Regardless of their immigration status, they are hunted down by militias loyal to Libya’s U.N.-backed government, caged in overcrowded prisons, and sold on open markets that human rights advocates have likened to slave auctions.” - P. Tinti (Foreign Policy, 2017)

In May 2017, in a sign of how much the situation in Libya had deteriorated, the International Criminal Court (ICC) informed the UN Security Council that it was exploring the feasibility of an investigation into “migrant-related crimes” in the country. The ICC also reported on its efforts to “liaise with Libyan national institutions, interested European organisations … as well as national judiciaries, to streamline the activities of European and other actors in the investigation and prosecution of crimes against migrants.”[8] Because many detention centres are under the control of militias, the ICC has called for “all detainees to be transferred to State authority, including … migrants detained for financial and political motivations.”[9]

With one of the world’s largest oil reserves, Libya has been an important destination for migrant labourers, attracting workers from neighbouring Arab countries since the 1960s. By 2009, there were some two million Egyptians in the country, most of whom worked irregularly. In the late 1990s, Muammar Gaddafi’s shift to Pan-Africanism drew a growing influx of migrants from sub-Saharan African countries. A policy volte-face in 2007 led to the imposition of visa regulations for both Arabs and Africans—the distinction between the two not always being clear—and with it, thousands of immigrants suddenly became “irregulars.”[10] During the 2011 uprising and ensuing civil war in Libya, close to 800,000 migrants fled, mainly to Tunisia and Egypt.[11]

Libya has more recently become a transit country for migrants from across Africa and from as far away as Syria. By late 2017, international organisations estimated that there were more than 400,000 migrants in Libya, among whom some 45,000 were registered as refugees or asylum seekers, according to UNHCR. The majority of migrants—approximately 60 percent—are from sub-Saharan countries.[12] However, the numbers of people embarking from Libya have begun to drop, as reflected in sharp declines of arrivals to Italy. As of mid-2018, some 20,000 people had arrived by sea; while there were nearly 120,000 arrivals in 2017 and more than 180,000 in 2016.[13] By mid-2018, IOM estimated at least 679,000 migrants in-country.[14]

The European Union (EU) began partnering with Libya in migration control efforts long before the onset of the current “refugee crisis.” Italian and EU arrangements with Gaddafi, including multi-million-Euro “migration management” projects, led to mass expulsions and a sharp increase in detention.[15] Observers argue that these “externalisation” efforts helped spur the creation of “one of the most damaging detention systems in the world.”[16]

Despite the widespread mistreatment of migrants in Libya and the on-going violence and social unrest since the overthrow of Gaddafi, Europe has continued to negotiate plans with various entities in Libya to check the flow of transiting foreigners.[17] These include an EU commitment to provide hundreds of millions of Euros to bolster the country’s detention infrastructure, to equip maritime forces to intercept smuggling boats, and to provide training on human rights standards to staff of Libya’s Department for Combatting Illegal Immigration (DCIM), which is ostensibly in charge of overseeing the country’s detention system.[18]

Deals have also been brokered with tribal authorities and militias linked to smuggling or human trafficking, who are closely interconnected with Libya’s detention system. As one source interviewed for this report said: “You said that some of the [facilities] have links to militias. I would push back and say, ‘Which facility does not have a link to a militia?’ … It’s impossible today to say that all of these security forces on interim contracts being paid by DCIM who are guarding these facilities are members of a proper security force.” [19]

In early 2017, the Italian government signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Libya's Government of National Accord (GNA) allowing the Libyan coastguard to intercept boats bound for Italy and return all those on-board to disembarkation zones in Libya, where they would subsequently be placed in detention. At the same time, Italy was paying rival militias to stop migrant boats in parts of the country not fully under government control, which have reportedly helped fuel armed conflict in these areas.[20]

The UN human rights commissioner has levelled severe criticism at these deals, arguing that the “increasing interventions of the EU and its member states have done nothing so far to reduce the level of abuses suffered by migrants.”[21] Despite the growing international outrage, an EU summit in mid-2018 “handed sea rescue mission responsibility” to the Libyan coastguard just as a new anti-immigrant Italian government began adopting a more heavy-handed approach that included blocking private vessels from docking asylum seekers in Italian ports.[22] Italy’s Interior Minister argued that all migrants rescued by European vessels should be sent back to Libya.[23]

International organisations have also been criticised for their role in Libya, in particular the IOM, which has been a key implementing partner for EU projects in the country. It has provided “human rights training” for detention centre staff, offered psychosocial support and healthcare, has helped renovate detention centres, and overseen an EU-financed “assisted voluntary return program,” which is one of the few ways migrants can exit detention centres. A journalist who visited Libyan detention centres quipped about the return program: “While many of the detained migrants I spoke with in Libya expressed a desire to go home after months of suffering in decrepit facilities, it’s unclear whether their return could ever be considered voluntary. Treat anyone bad enough and they will beg to make it stop.”[24]

For its part, the IOM vociferously defends its operations in Libya, arguing that they cannot choose with whom they work in detention centres and that they are “one of a few humanitarian organizations providing aid inside.”[25] Said the IOM's operations officer for Libya, “We are not the body that determines what is a detention center and what is not.”[26] The organisation has criticised the automatic confinement of “rescued” migrants in Libyan detention centres and called for finding “alternatives,” including re-opening an IOM-run shelter.[27]

The proliferation of actors involved in the detention of non-citizens in Libya raises a number of concerns related to oversight, jurisdiction, and accountability, as well as the real possibility that any external support for detention will inexorably amount to support for criminal activities. Pointing to militia involvement in operating detention centres in Libya—in addition to the roles played by the IOM and other non-state actors—one writer argues that the close association between detention and criminality in the country raises disturbing questions about the implications of Europe’s financing of migration control: “In many countries that are targeted for more migration management assistance—like Libya—there appears to be an inevitable connection between legal and illicit forms of detention and removal because of pervasive lawlessness and corruption.”[28]

:: Read the full report as PDF

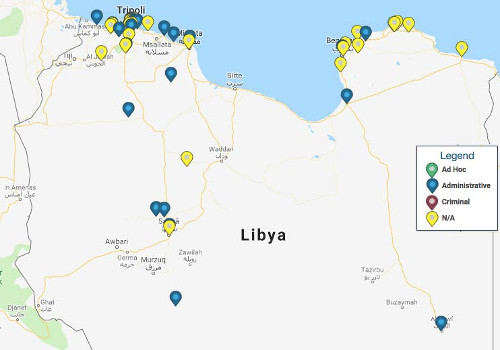

Immigration detention facilities in Libya (Global Detention Project / Google Maps)

Notes

[1] United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), “UN Report Urges End to Inhuman Detention of Migrants in Libya,” http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=21023&;LangID=E

[2] United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL), “Remarks of SRSG Ghassan Salame to the United Nations Security Council on the situation in Libya,” 16 July 2018, https://unsmil.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/srsg-ghassan-salame-briefing-unsc-20180716.pdf; United Nations Security Council (UNSC), “Report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Support Mission in Libya,” 5 September 2014, http://undocs.org/S/2014/653; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). “UNHCR Position on Returns to Libya,” 12 November 2014, http://www.refworld.org/docid/54646a494.html; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “Libya Factsheet,” February 2015, www.reliefweb.int/report/libya/unhcr-factsheet-libya-february-2015; Human Rights Watch (HRW), “Libya: Whipped, Beaten, and Hung from Trees,” 22 June 2014, http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/06/22/libya-whipped-beaten-and-hung-trees; Amnesty International, “Amnesty International Report 2013: The State of the World’s Human Rights,” 23 May 2013, https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/pol10/001/2013/en/

[3] Associated Press, “Italian Effort to Stop Migrants Fuels Bloody Battle in Libya,” 5 October 2017, https://www.voanews.com/a/libya-militias-migrants-sabratha/4057716.html

[4] InfoMigrants, “Up to 10,000 Migrants in 20 Centers Under the Sun, IOM Libya,” 3 July 2018, http://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/10363/up-to-10-000-migrants-in-20-centers-under-the-sun-iom-libya; Amnesty International, “Libya’s Dark Web of Collusion: Abuses Against Europe-Bound Refugees and Migrants,” 11 December 2017, https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/MDE1975612017ENGLISH.PDF

[5] Journalist Peter Tinti, in an investigative report for Foreign Policy magazine published in October 2017,put it this way: “Eighteen months after the EU unveiled its controversial plan to curb illegal migration through Libya—now the primary point of departure for sub-Saharan Africans crossing the Mediterranean Sea to Europe—migrants have become a commodity to be captured, sold, traded, and leveraged. Regardless of their immigration status, they are hunted down by militias loyal to Libya’s U.N.-backed government, caged in overcrowded prisons, and sold on open markets that human rights advocates have likened to slave auctions. They have been tortured, raped, and killed— abuses that are sometimes broadcast online by the abusers themselves as they attempt to extract ransoms from migrants’ families.” See: P. Tinti, “Nearly There, but Never Further Away,” Foreign Policy, 5 October 2017, http://europeslamsitsgates.foreignpolicy.com/part-3-nearly-there-but-never-further-away-libya-africa-europe-EU-militias-migration

[6] Al Jazeera, “Libya: The Migrant Trap,” 8 May 2014, http://www.aljazeera.com/programmes/peopleandpower/2014/05/libya-migrant-trap-20145483310400633.html; R. Seymour, “Libya's Spectacular Revolution has been Disgraced by Racism,” The Guardian, 30 August 2011, http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2011/aug/30/libya-spectacular-revolution-disgraced-racism

[7] International Organisation for Migration (IOM), “IOM Learns of 'Slave Market' Conditions Endangering Migrants in North Africa,” 4 November 2017, https://www.iom.int/news/iom-learns-slave-market-conditions-endangering-migrants-north-africa

[8] The Office of the Prosecutor, “Fifteenth Report of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court to the United Nations Security Council Pursuant to UNSCR 1979 (2011),” International Criminal Court, 9 May 2018; United Nations Security Council (UNSC), “Report of the Security-General on the United Nations Support Mission in Libya,” 22 August 2017, https://unsmil.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/n1725784.pdf

[9] International Criminal Court (ICC), “Eleventh Report of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court to the United Nations Security Council Pursuant to UNSCR 1970 (2011),” 26 May 2016, https://www.icc-cpi.int/Pages/item.aspx?name=otp_report_lib_26052016

[10] P. Fargues (ed.), “EU Neighbourhood Migration Report 2013,” European University Institute, Migration Policy Centre, 2013, http://www.migrationpolicycentre.eu/migration-report/; A. Di Bartolomeo, T. Jaulin, and D. Perrin, “CARIM – Migration Profile Libya,” Consortium for Applied Research on International Migration (CARIM), June 2011, http://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/22438

[11] International Organisation for Migration (IOM), “Report of the Director General on the Work of the Organization for the Year 2011,” June 2012, http://governingbodies.iom.int/system/files/jahia/webdav/shared/shared/mainsite/about_iom/en/council/101/MC_2346.pdf

[12] Amnesty International, “Libya’s Dark Web of Collusion: Abuses Against Europe-Bound Refugees and Migrants,” 11 December 2017, https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/MDE1975612017ENGLISH.PDF

[13] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “UNHCR Flash Update: Libya, 20-27 July 2018,” 27 July 2018, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/UNHCR%20Libya%20Flash%20Update%2027%20July%202018.pdf; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “Operational Portal: Mediterranean Situation,” http://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean/location/5205

[14] International Organisation for Migration (IOM), “Libya,” Displacement Tracking Mechanism (DTM), June 2018, http://www.globaldtm.info/libya/

[15] European Commission (EC), “Annex of the Commission Implementing Decision on the Annual Action Programme for 2013 (Part 2) in Favour of Libya [C(2013) 9196 final]. Action Fiche for Support to Rights-Based Migration Management and Asylum System in Libya,” December 2013, https://bit.ly/2KA4XzW; Danish Refugee Council and Danish Demining Group (DRC/DDG), “2014: Strategic Programme Document – DRC/DDG in Libya and Tunisia,” https://drc.ngo/media/1194589/libya-tunisia-strategic-programme-document-2014.pdf

[16] H. Van Aelst, “The Humanitarian Consequences of European Union Immigration Policy’s Externalisation in Libya: The Case of Detention and its Impact on Migrants’ Health,” BSIS Journal of International Studies, Vol. 8, 2011 University of Kent, Brussels School of International Studies, 2011, https://www.kent.ac.uk/brussels/

[17] Human Rights Watch (HRW), “Libya: Whipped, Beaten, and Hung from Trees,” 22 June 2014, http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/06/22/libya-whipped-beaten-and-hung-trees; Amnesty International, “Amnesty International Report 2013. The State of the World’s Human Rights,” 23 May 2013, https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/pol10/001/2013/en/; Council of the European Union (CEC),”Council Conclusions on Libya. Foreign Affairs Council meeting 20 October 2014,” October 2014, http://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/25118/145200.pdf; C. Malmström, “Answer Given by Ms Malmström on Behalf of the Commission,” European Parliament, 12 June 2014, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getAllAnswers.do?reference=E-2014-002692&;language=EN

[18] European Union, “Factsheet: EU-Libya Relations,” 22 January 2018, https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage_en/19163/EU-Libya%20relations,%20factsheet; P. Tinti, “Nearly There, but Never Further Away,” Foreign Policy, 5 October 2017, https://bit.ly/2fUztGs

[19] Anonymous source (representative from international human rights group), Skype call with Tom Rollins (Global Detention Project), May 2018.

[20] Associated Press, “Italian Effort to Stop Migrants Fuels Bloody Battle in Libya,” 5 October 2017, https://www.voanews.com/a/libya-militias-migrants-sabratha/4057716.html

[21] United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, “UN Human Rights Chief: Suffering of Migrants in Libya Outrage to Conscience of Humanity,” 14 November 2017, http://www.ohchr.org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=22393&;LangID=E

[22] B. Riegert, “Libya Takes Over from Italy on Rescuing Shipwrecked Migrants,” Deutsche Welle, 5 July 2018, https://www.dw.com/en/libya-takes-over-from-italy-on-rescuing-shipwrecked-migrants/a-44546754

[23] InfoMigrants, “Salvini calls for migrants to go back to Libya,” 17 July 2018, http://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/10685/salvini-calls-for-migrants-to-go-back-to-libya

[24] P. Tinti, “Nearly There, but Never Further Away,” Foreign Policy, 5 October 2017, http://europeslamsitsgates.foreignpolicy.com/part-3-nearly-there-but-never-further-away-libya-africa-europe-EU-militias-migration

[25] O. Belbesi, “Returned to Libyan Shores and Held in Detention Centres: What are the Practical Alternatives?” IOM Libya/Reuters, 18 August 2018, https://news.trust.org/item/20180816142408-bats4/

[26] P. Tinti, “Nearly There, but Never Further Away,” Foreign Policy, 5 October 2017, http://europeslamsitsgates.foreignpolicy.com/part-3-nearly-there-but-never-further-away-libya-africa-europe-EU-militias-migration

[27] O. Belbesi, “Returned to Libyan Shores and Held in Detention Centres: What are the Practical Alternatives?” IOM Libya/Reuters, 18 August 2018, https://news.trust.org/item/20180816142408-bats4/

[28] M. Flynn, “Kidnapped, Trafficked, Detained? The Implications of Non-state Actor Involvement in Immigration Detention,” Journal on Migration and Human Security, 2017, http://cmsny.org/publications/jmhs-kidnapped-trafficked-detained/